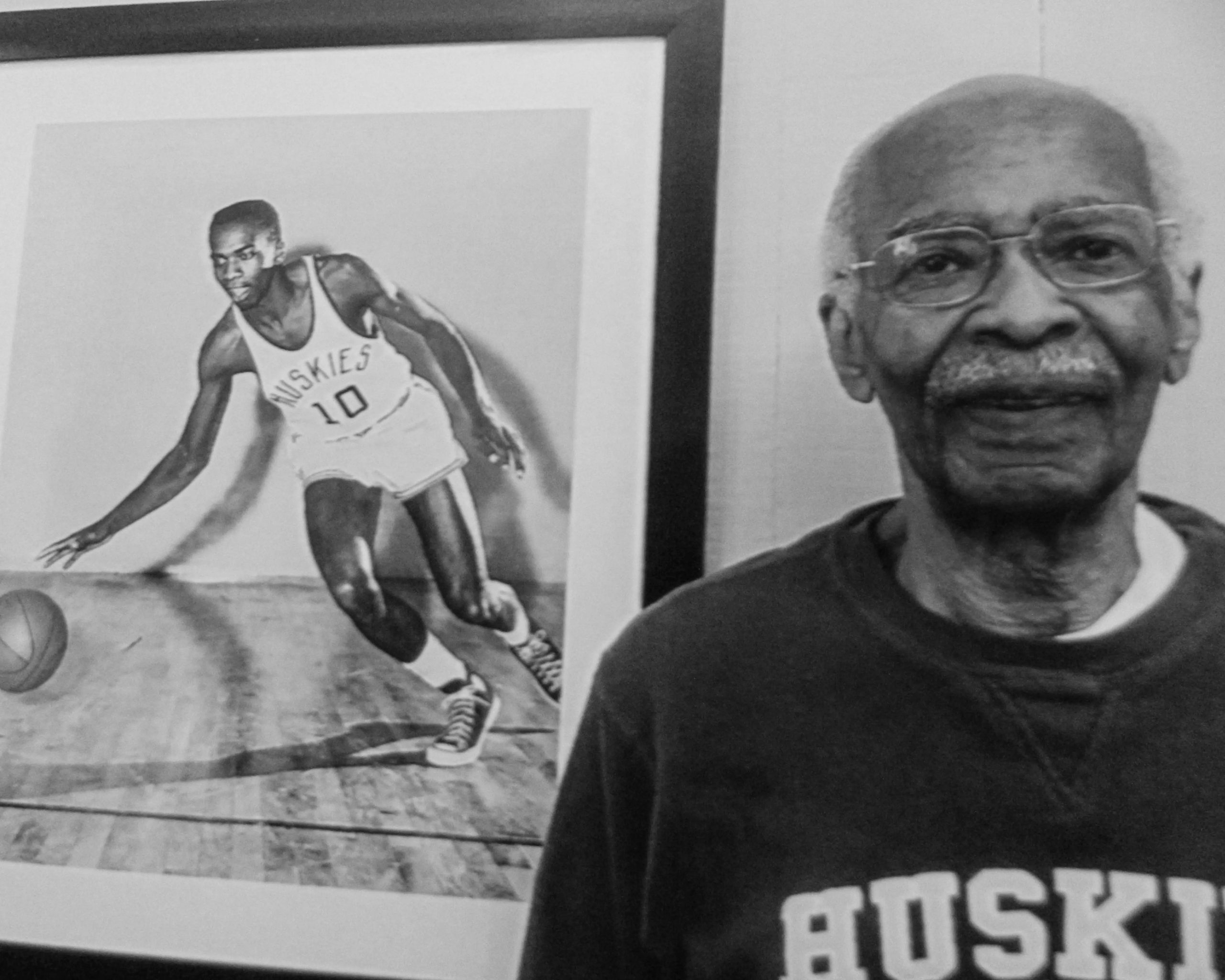

Richard “Dick” Crews

Dick Crews (1936-2011)

When I see the phrase “the first African American” to accomplish an act, I celebrate and think about those years of doors being closed to African Americans in that field. The reason those doors were closed was not that we were unqualified. It was because we were viewed as inferior and laws were in place to keep us as second-class citizens.

With each “first” I see I also continue to ignore the malcontents that complain and attempt to view these celebrations as being divisive. You see, my celebration of that “first” — today another former Bremerton resident who made history beyond this county — is relevant to every little Black boy or Black girl who may then say, “I will do that and more someday.”

Richard “Dick” Crews was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, and his family moved to Bremerton, settling in Sinclair Heights, when Dick was young. His family was part of the Great Migration of African Americans moving from the South in the 1940s. His father worked at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, and after World War II ended the family moved to Seattle.

The Crews maintained contact with the Cleveland and Tessie Williams family in Bremerton, and eventually daughter Norma married Dick. She was the love of his life, and passed in 2011.

In 1954 Dick graduated from Garfield High, where he played basketball and ran track and field, was a member of the Honor Society and earned an academic scholarship from the Carnation Company.

Dick enrolled at the University of Washington in 1955 and became the first African American to play basketball for the Huskies. He joined the UW freshman team as a non-scholarship player and became a starter. However, it didn’t happen without intense negotiation between Garfield High’s coach, Bob Tate, and others encouraging UW coach Tippy Dye to do the right thing and allow Dick to play. When Tate asked Tippy, “Why wouldn’t you keep him on the team when he is your best player?” Tippy replied, “There are some alums who don’t want to see him represent the university.” With more lobbying by others, the coach gave in.

Along the way, there were insensitive moments. While traveling to play Oklahoma State, the team was refused service at an Oklahoma City restaurant because of the presence of Crews. A waitress ran up to the bus after seeing Crews and said the restaurant was closed, although it was noontime. The team went to another restaurant, which allowed him to eat in a back room, so far back that nobody could see him. Around the UW campus, he often heard the “N word,” once by a teammate in front of him in the training room. He admonished the guy and received an apology. While at UW, Dick earned three varsity letters; he was named inspirational player twice and was honored for having the highest GPA on the team.

Crews didn’t let anyone deny him anything while in college. Besides graduating in four years with a history degree, he served as the first African American student body vice president, alongside president and future Washington Governor Booth Gardner.

After graduation, Dick worked as assistant director of development at UW and later worked at the Weyerhaeuser company as a sales trainer with territories in Washington, Oregon and parts of Alaska. Among his other accomplishments were serving as a trustee with the UW Alumni Association, president of the UW Quarterback Club Board, and supporting UW alumni multicultural activities and recruiting, mentoring and supporting diverse students, faculty and staff at Washington. And last fall, Crews was Dick Crews honored with the Don H. Palmer Award, recognizing those who have exemplified a special commitment to the UW Athletic Department.

Dick is currently retired and living in Renton and likes to say, “Once a Husky, always a Husky.”

When I celebrate Dick Crews, or any others, from being the “first” in a field it means we realize that biases, prejudice, discrimination and racism have existed and still exist. Anyone telling us what we are experiencing is not real is ludicrous. Anyone tired of seeing celebrations of an African American as a “first” should learn more about our history. Possibly, that would help them understand that African Americans are not to blame for those celebratory acknowledgements, but celebrating because another barrier was cracked. We have been trying to tear down walls for centuries, and we are going to continue to do so in every facet of American life.