Who is a Pioneer?

The word “pioneer” has several definitions and its meaning to each of us is as personal and individual as we are. However, there is one definition that applies to all pioneers: a person who goes before, preparing the way for others.

As you scroll through this exhibit, consider the ways that Filipino Americans have “gone before,” into unfamiliar and hostile territory to prepare the way for future generations.

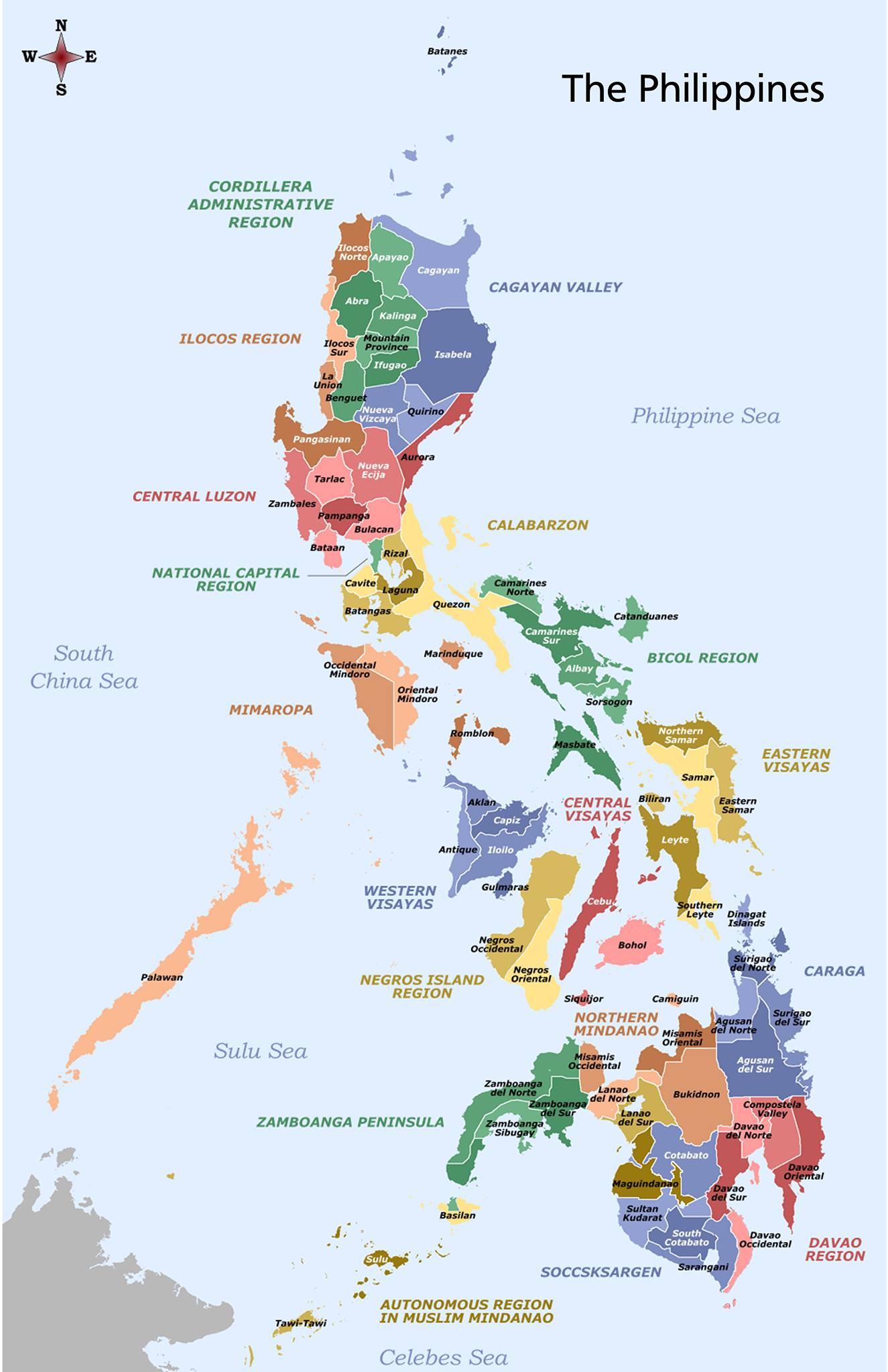

The Philippines

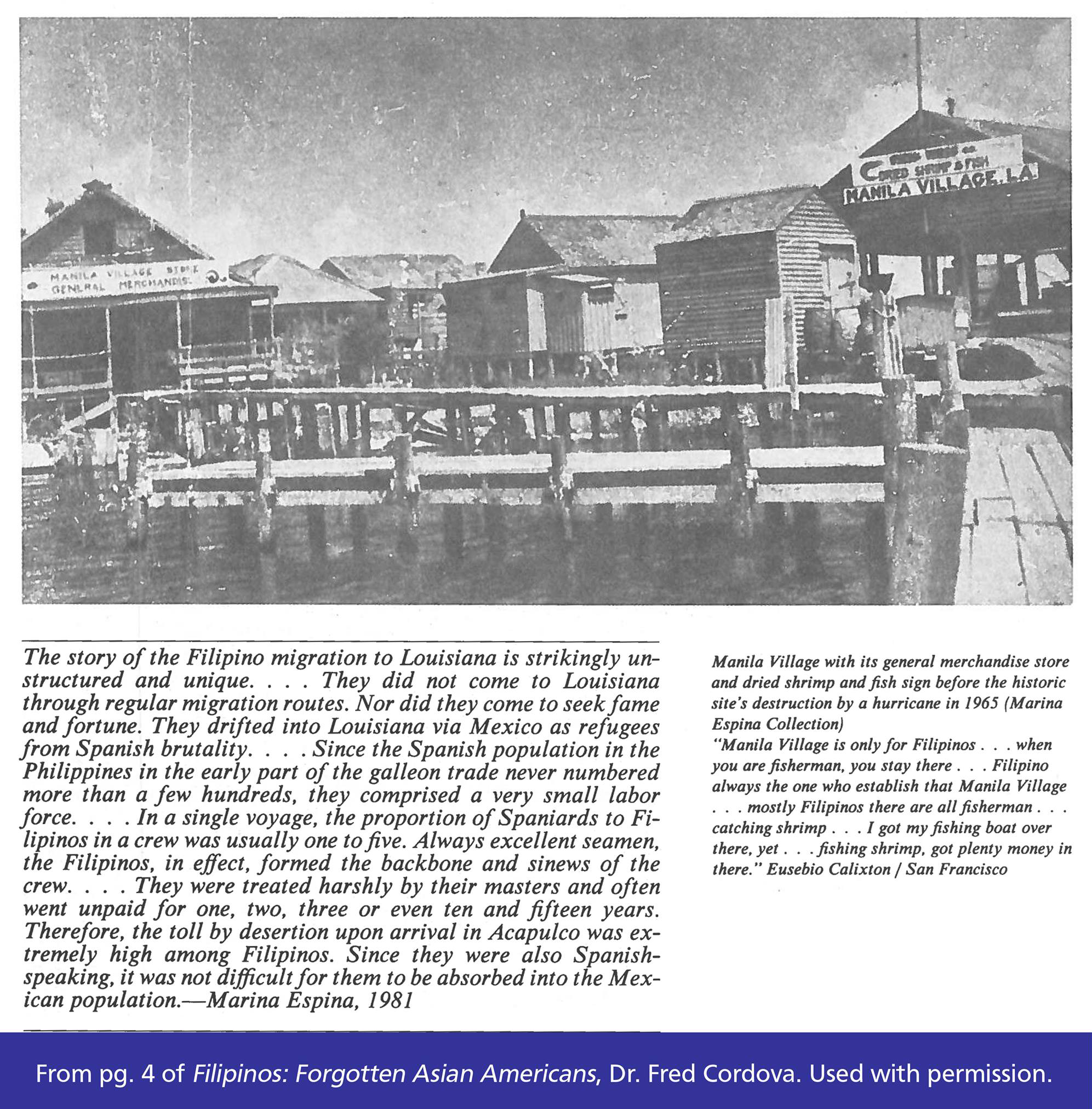

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country of over 7,000 islands in the Western Pacific. The cultural diversity of the islands include over 170 ethno linguistic groups. The country was named in honor of Spain’s King Philip II during Ruy López de Villalobos’ 1542 expedition. From 1565 – 1898, the people of the Philippines lived under Spanish colonial rule. The Spanish used religion-based compulsory education, forced labor, and intimidation to establish colonial dominance. These served as a means of control to stifle indigenous cultural practices and subjugate the native people. The Manila Galleon Trade redirected labor resources that would have supported the traditional agrarian economy.

The Manila Galleon trade brought the first Filipinos to what is now known as the United States 30 years before the pilgrims arrived. Filipinos fled Spanish ships into Mexico to escape the brutal conditions of slavery.

The Spanish American War

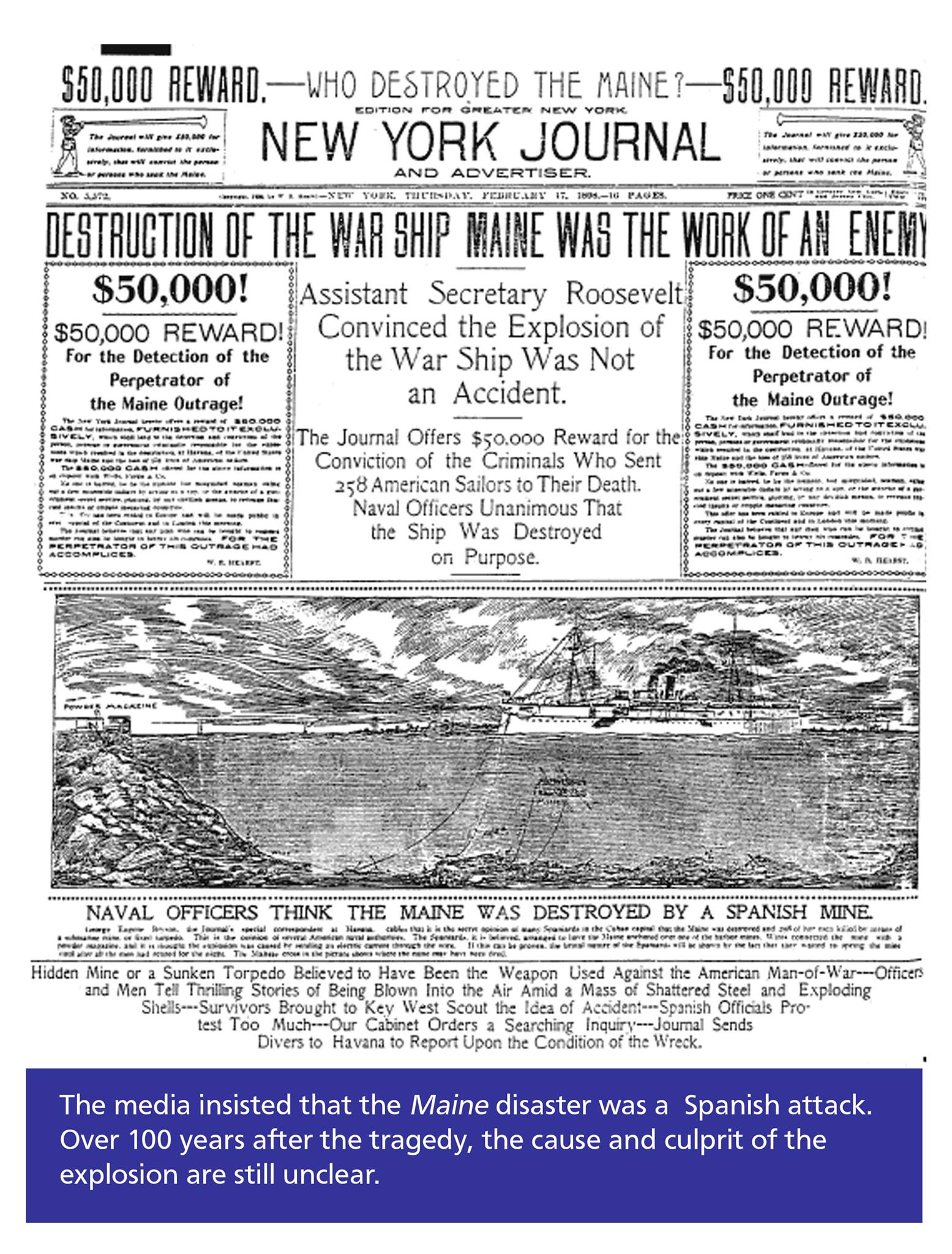

The Spanish American War was sparked in 1895, when Cuba struggled for independence from Spain. U.S. newspapers graphically portrayed Spain’s treatment of Cuban rebels, garnering support for U.S. involvement from the American people.

On February 15, 1898, a sudden explosion on an American battleship stationed in Havana Harbor killed three quarters of the crew. The U.S.S. Maine was protecting U.S. interests in Cuba when the tragedy occurred. Appealing to American patriotism and revenge, sensationalist newspapers known as the “yellow press” presented the explosion as a Spanish strike against the U.S. The sinking of the Maine was the catalyst for the end of diplomatic relations between Spain and the U.S. In early April of 1898, Congress issued resolutions declaring Cuba’s right to independence and demanded that Spain withdraw forces from the island. Spain declared war on the United States on April 24, 1898.

Fighting for Freedom?

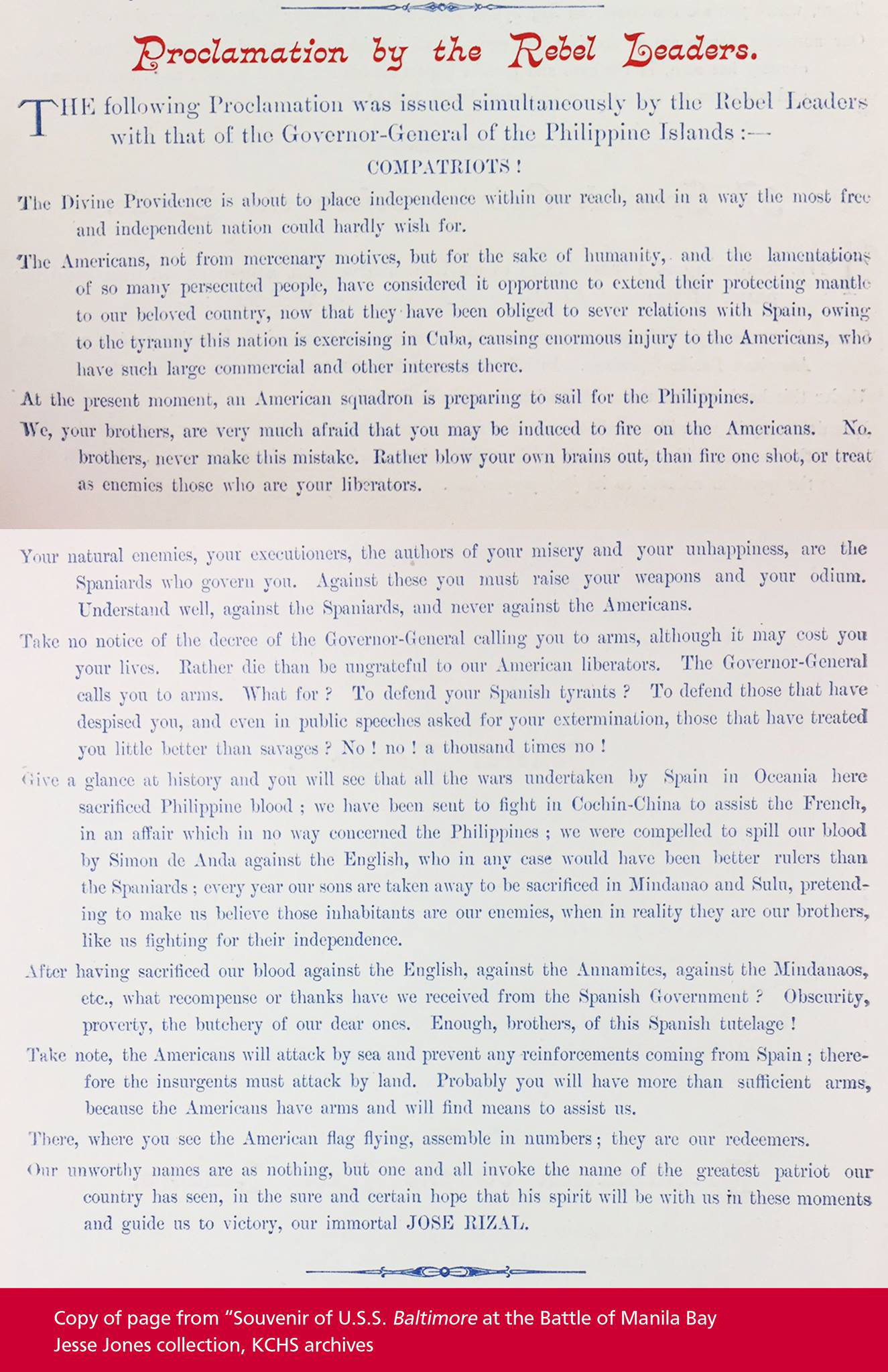

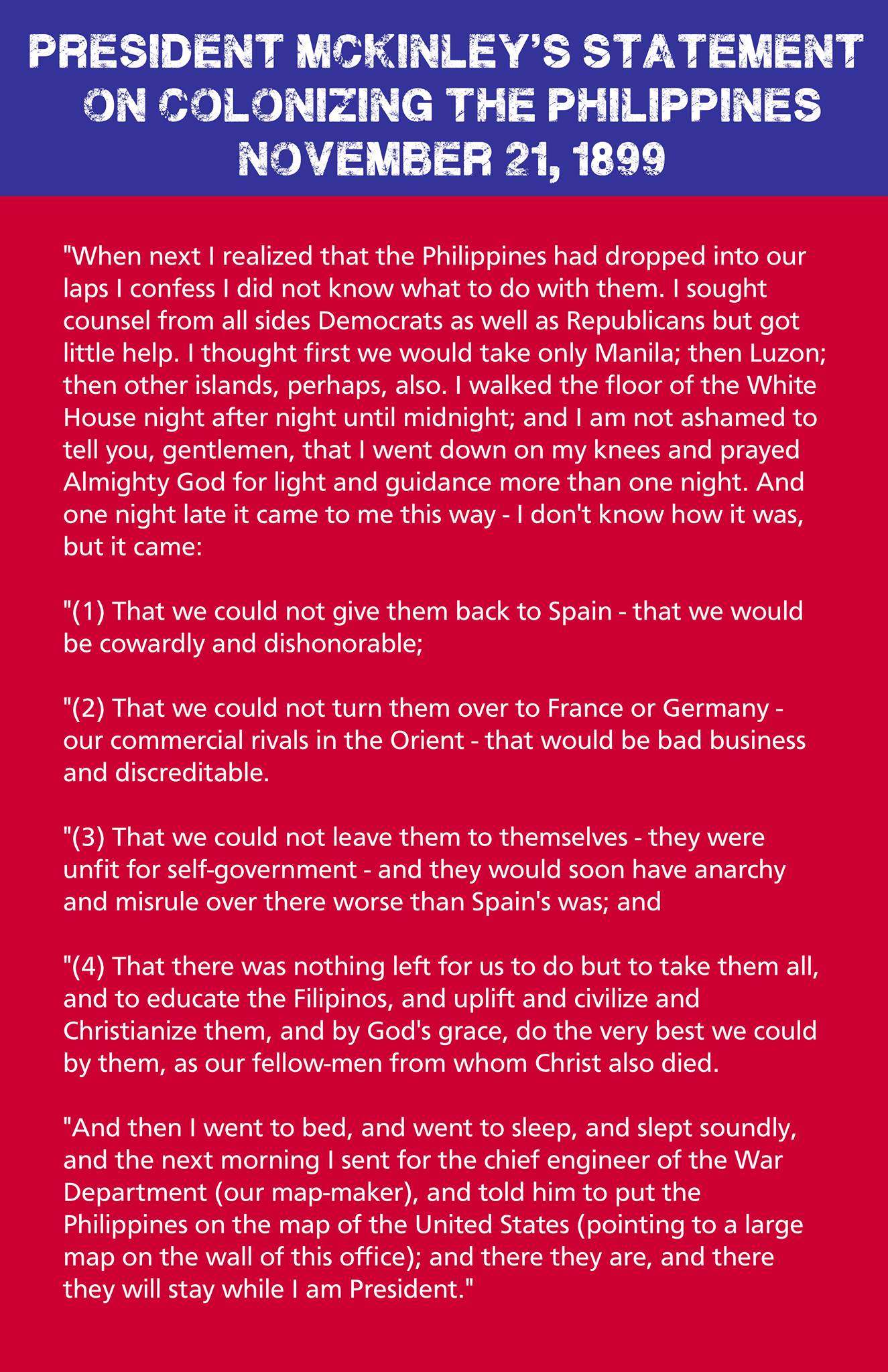

By the time the U.S. entered the Philippines to remove Spanish forces, Philippine revolutionary groups had already positioned the country for independence but had been unable to militarily defeat Spain. After Commodore Dewey defeated Spain at Manila Bay, Philippine rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo made contact with U.S. forces and arranged to assist them in their fight against Spain, believing that the war would end with Philippine independence.

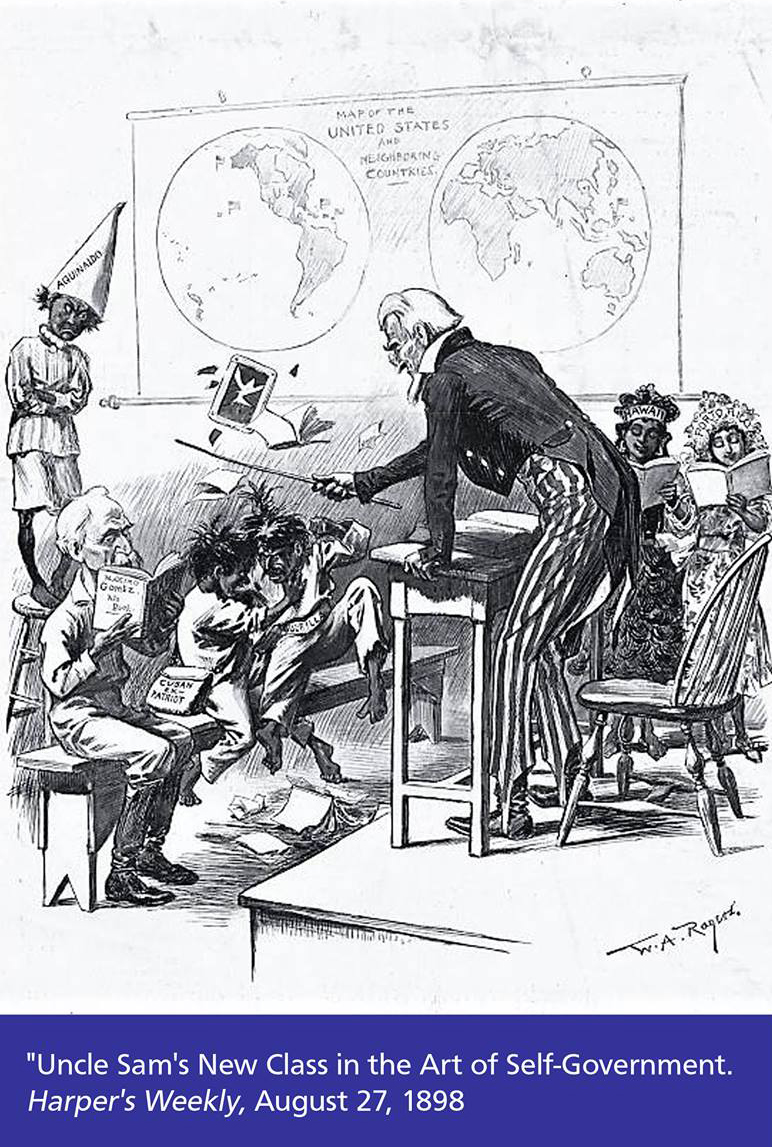

After learning that independence wasn’t part of the deal, Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines. Working with Malolos Congress, he drafted a constitution for a new republic, declaring Philippine Independence on June 12, 1898. The Philippines was now an independent, self-governing nation.

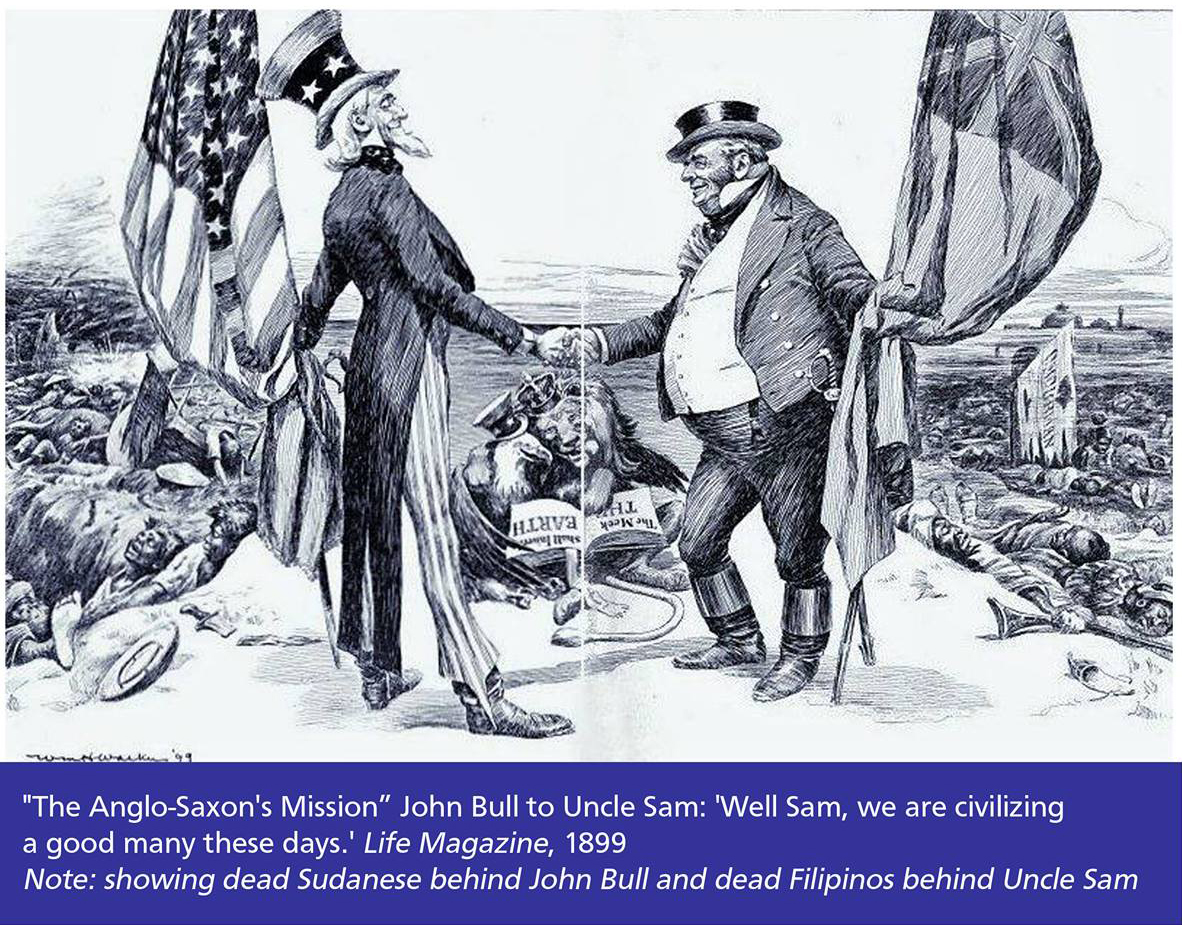

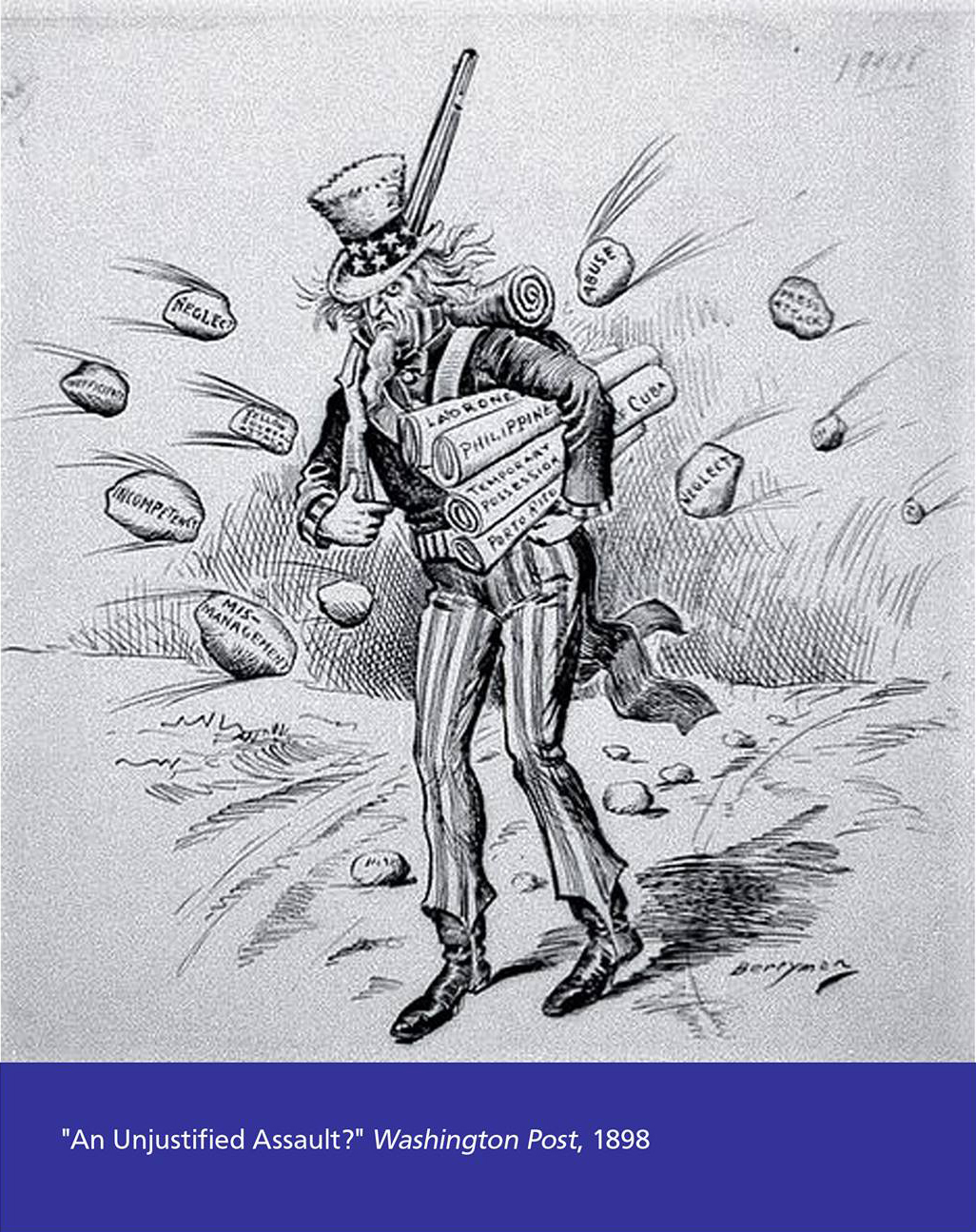

However, while Spanish and American forces fought in the Philippines, Spain ceded Cuba and Puerto Rico to the United States and sold the Philippines for $20 million in the Treaty of Paris in December 1898. Ambassadors from The Philippine Republic asked president McKinley that they be allowed to represent their people but were excluded from Spanish American negotiation sessions. Ultimately all pleas from Filipino delegates in the Paris negotiations were discarded and the Philippine Republic became a U.S. territory.

Philippine-American War

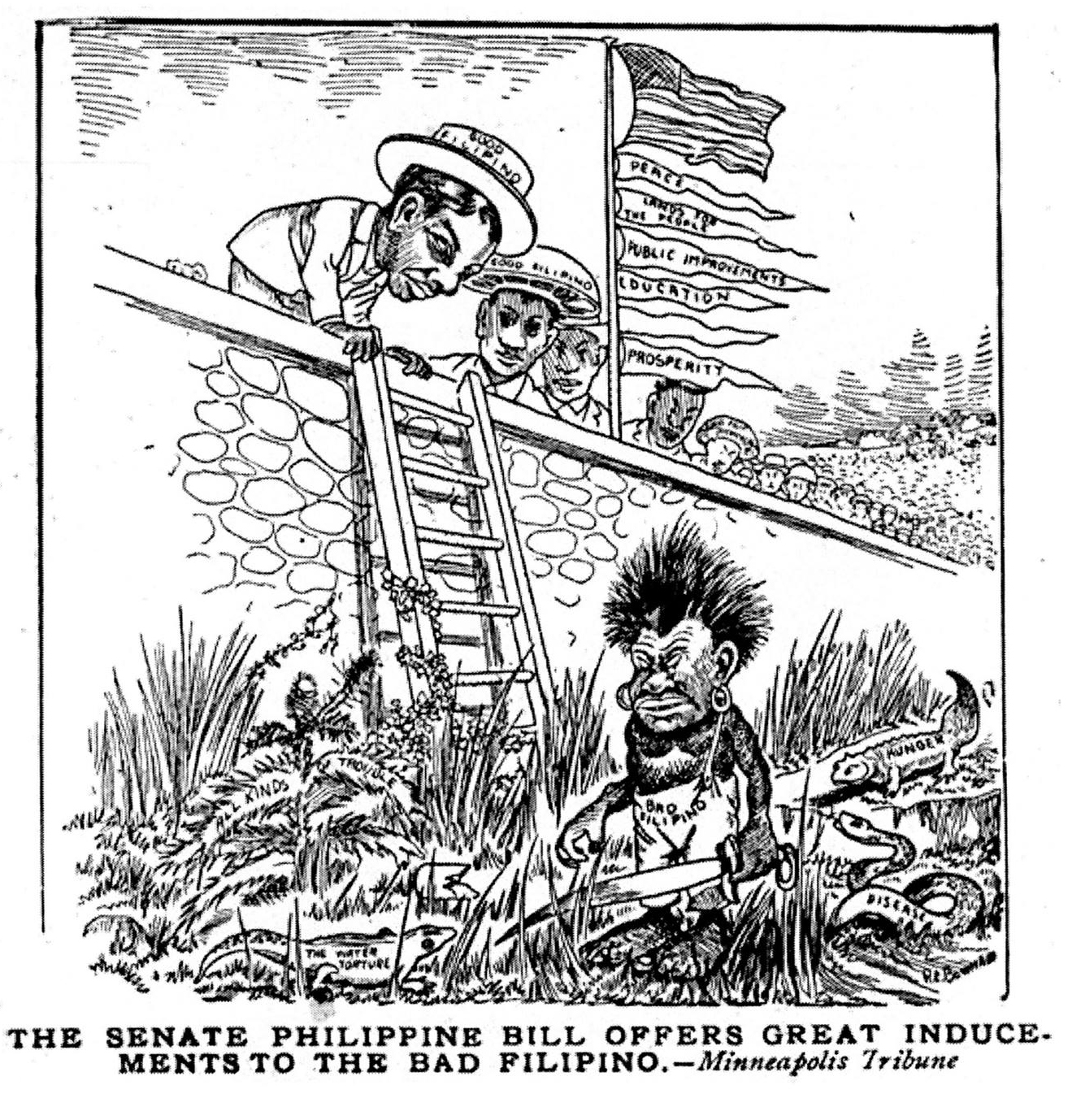

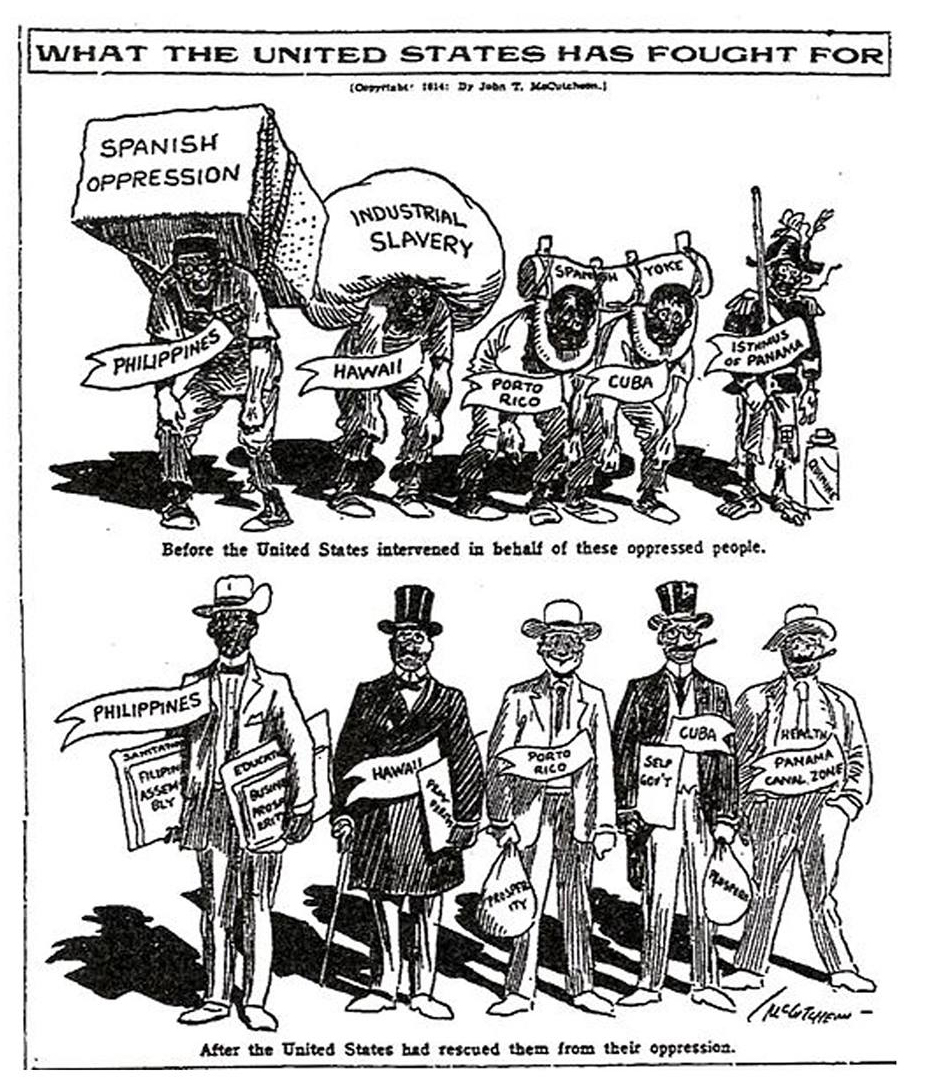

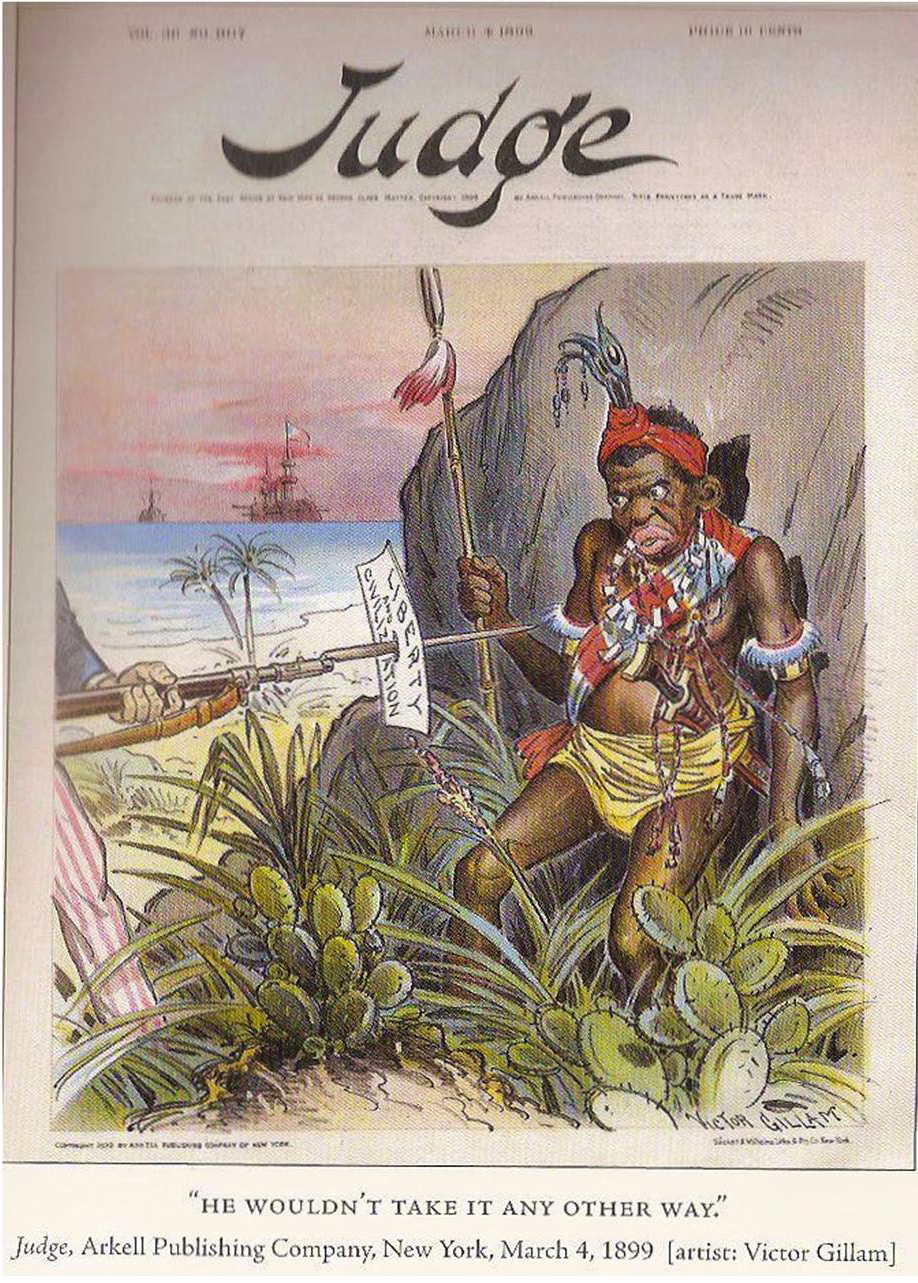

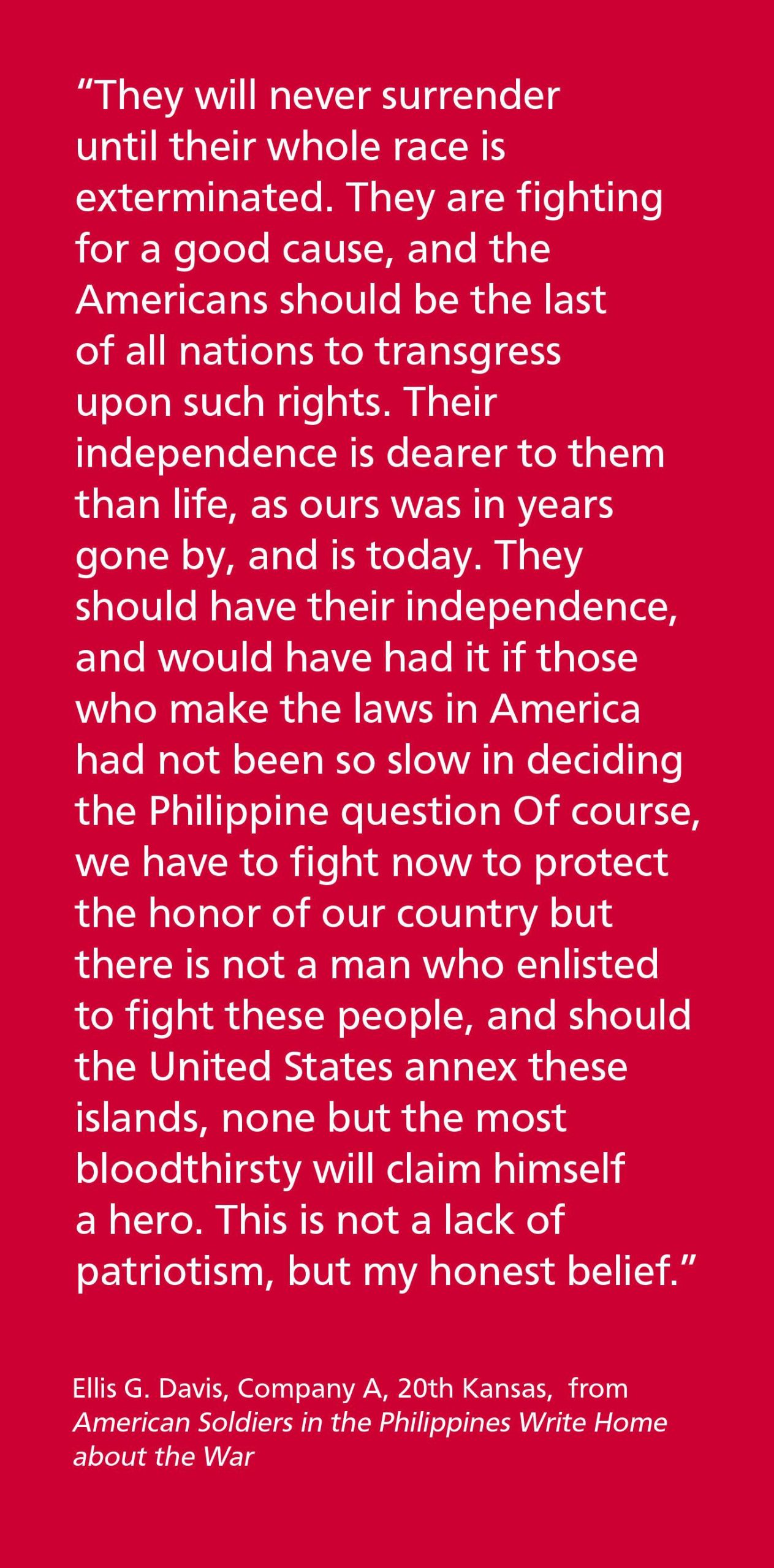

The United States’ imperialist agenda to extend reach across the Pacific resulted in the Philippine-American War. Emilio Aquinaldo was inaugurated as President of the Philippine Republic in January of 1899. Two weeks later, an American sentry killed a Philippine soldier as a statement against Philippine independence. Where once soldiers were fighting alongside Filipinos, they were now fighting against them. The war lasted three years and resulted in over 200,000 Filipino civilian deaths. Many Americans were against the war, stating that the imperialist agenda of United States presence in the Philippines went against American values. Others supported taking the islands for trade and military purposes. President Roosevelt proclaimed an end to the insurrection on July 4, 1902. The United States then attempted to “civilize” the people of the Philippines. Children were forced to speak English in their classrooms and would suffer corporal punishment and humiliation if they spoke their native language. The idea of “The American Dream” was instilled, and the United States was portrayed as a promised land of opportunities.

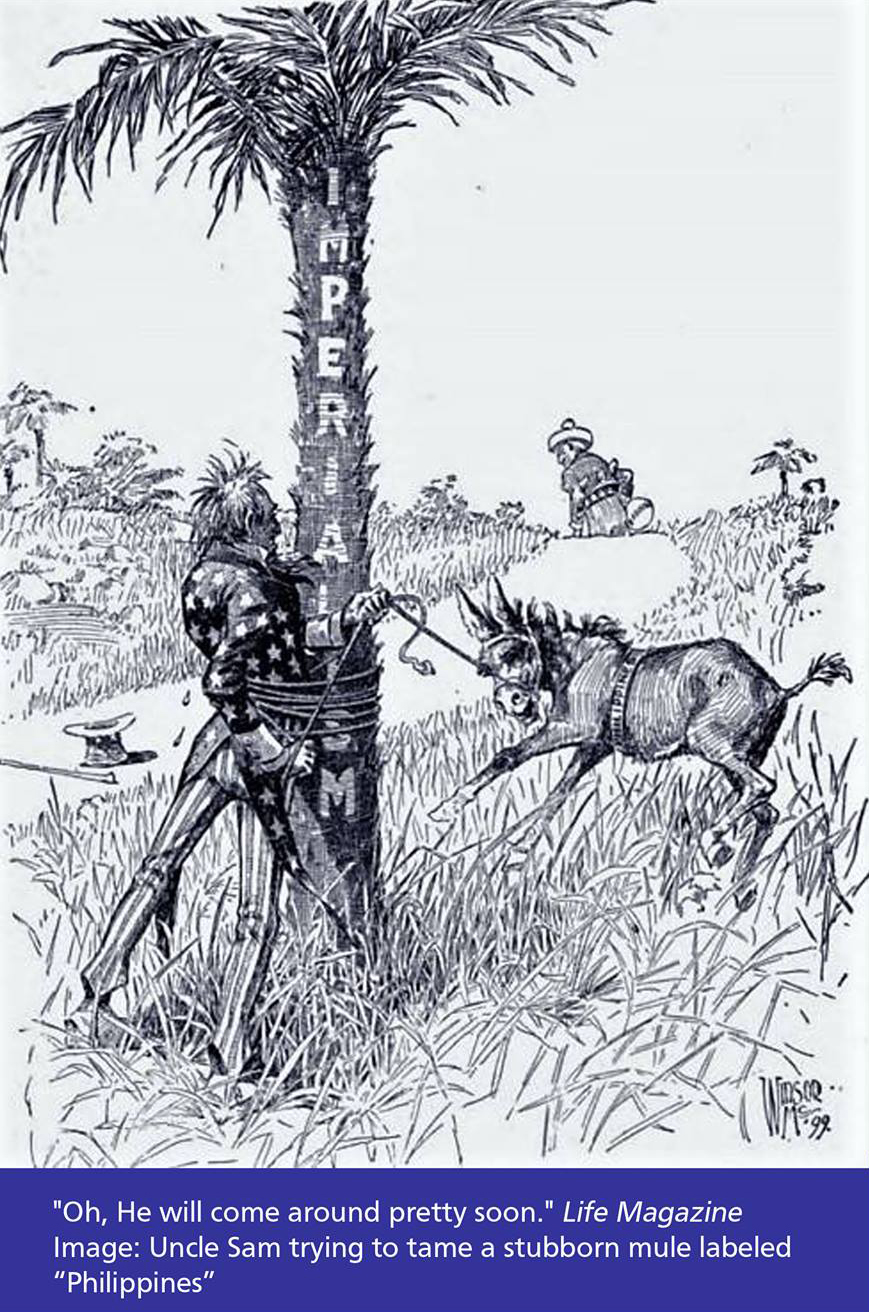

Political cartoons reflected the conflicting viewpoints of Americans

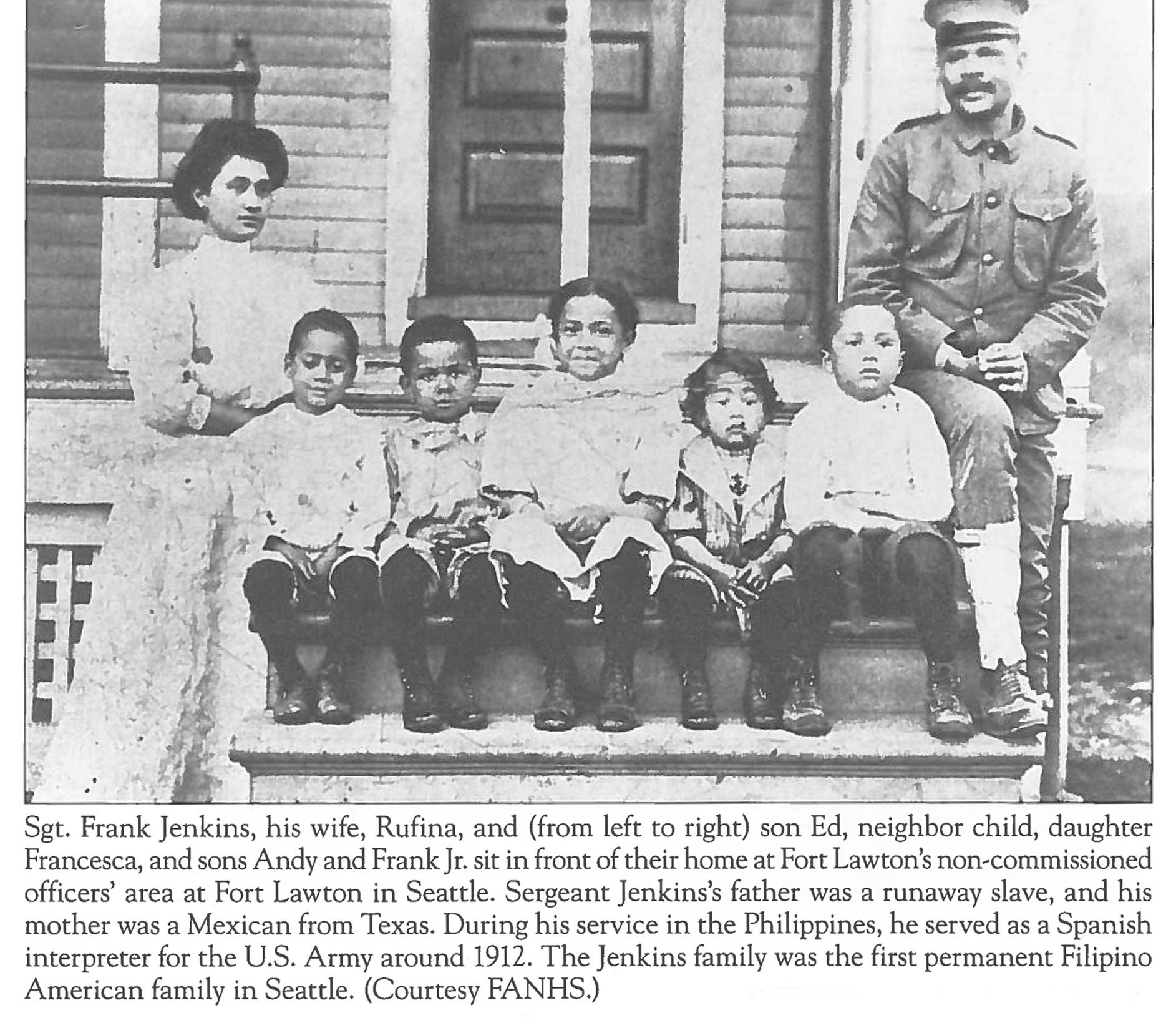

War Brides

Some American veterans of the Philippine American War married Filipinas and brought them home. Photo from Filipinos in Puget Sound, by Dorothy Laigo Cordova and the Filipino American National Historical Society. Used with permission.

Filipino Migration to the United States

Although Filipinos first settled permanently in the United States in the 18th century, the first large immigration wave began in 1906 with the Sakadas (agricultural workers). With U.S. presence and education in their home country, and their status of U.S. nationals, Filipinos began to migrate to the U.S. in search of The American Dream. They were entitled to the same protections under the Bill of Rights as any U.S.citizen.

Filipinos, as U.S. nationals, did not have to go through customs to enter the country. This was one factor that led to the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association’s (HSPA) recruitment campaign in Manila.

In 1906, the first 15 Filipino sugar plantation laborers arrived in Hawaii. By 1919, more than 29,000 Filipinos had traveled to Hawaii to take labor contracts. Predominately single males, these sakadas planned to save their earnings to pay for a college education in the U.S. or take back home to build a better life, buy land, and get married.

Some sakadas achieved their goals, but many more found The American Dream out of reach. Labor exploitation and prejudice made it impossible for many sakadas to save enough money to begin their education or pay for passage back home.

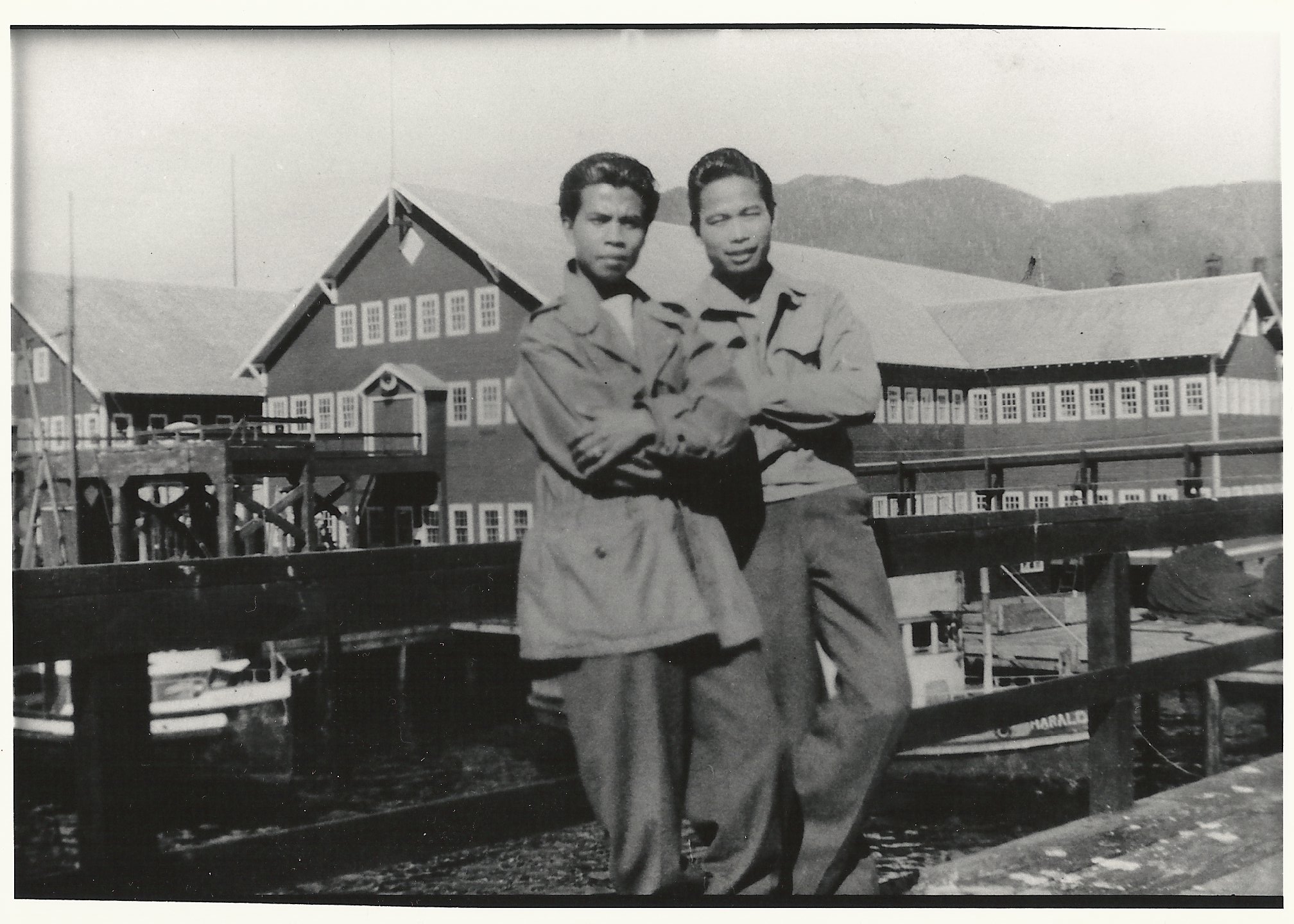

Rosendo Berganio of Bainbridge Island with an unidentified man at the Alaskan Cannery he worked at seasonally.)

After WWI through 1930, Filipinos traveled to California, Washington, and other parts of the continental United States to work in the agricultural fields.

Many of these Second-Wave Filipino migrants stated “education” as their reason for coming to the United States. These Pensionados came to attend American colleges and universities on Philippine government pensions with the understanding that they would return to the Philippines to contribute their professional skills to the nation’s wellbeing. This group would lay the groundwork for Filipino community organizations through campus clubs and publications. The Depression forced many Pensionados to temporarily turn away from their studies to survive the economic climate.

Those impacted often took seasonal jobs in Alaskan canneries to fortify their income. The nationwide dispatching point for Alaskan cannery workers was in Seattle.

UNION ACTIVISM

Filipino Americans have a long history of revolting against injustice. These are a small sample of labor uprisings facilitated by Filipino Americans:

– In the 1920s, Pablo Manlapit organized HSPA workers to strike and demand better wages and working conditions, forming the Hawaiian Sugar Workers Union.

– In the 1930s, agricultural workers Rufo Canete, D.L. Marcuelo, Tomas Lascetonia, Johnny Estigoy, Nick Losada, and Alfonso Castillo formed the Filipino Labor Union.

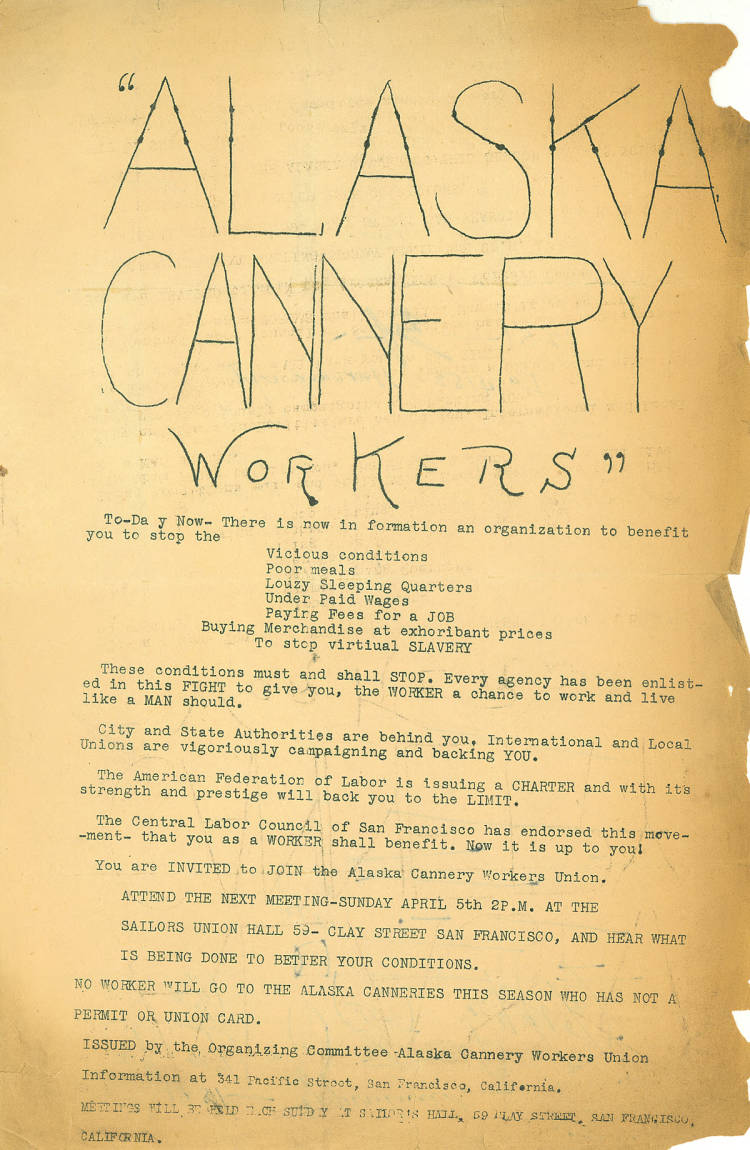

-In 1933, Alaskeros formed the Alaskan Cannery Workers Union

-In 1959, labor leaders Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and Pete Velasco joined with the AFL-CIO to create the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association joined AWOC in the Delano Grape Strike and the two organizations merged to become United Farm Workers Union.

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, PNW01233

The Great Depression and Immigration Quotas

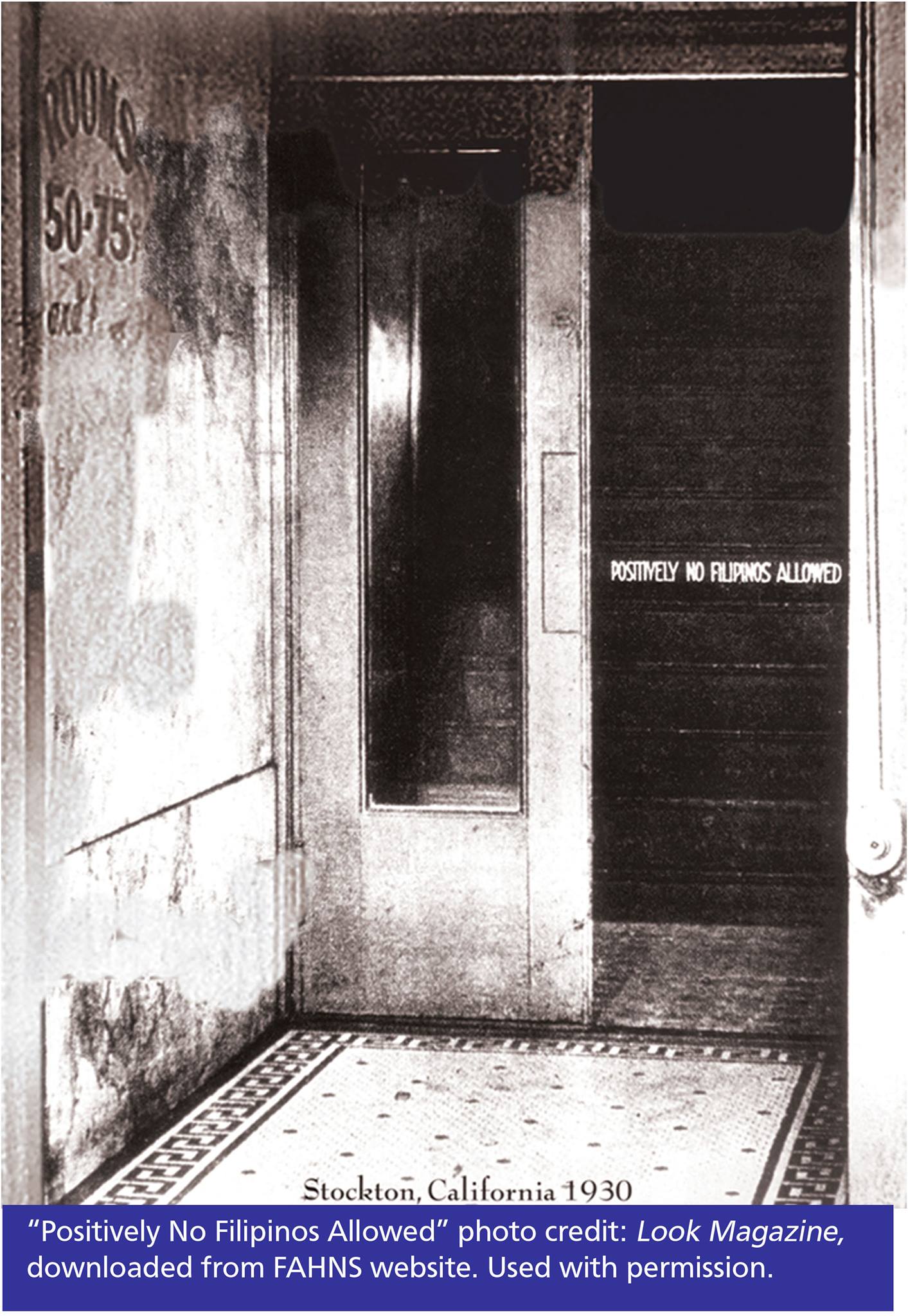

The Great Depression brought a new set of challenges to Filipino Americans. With the country in economic crisis, white Americans set out to find a scapegoat. They accused Filipino Americans of taking jobs from white men, “stealing” white women, and described them as “little brown monkeys” who were unclean, uneducated, and unethical. Although Filipinos were in the U.S.as nationals protected by the Bill of Rights, much of white America did not want them here. In 1934, Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act. The law was a double-edged sword in that it promised Philippine Independence in 10 years and categorized the country as a Commonwealth but changed the status of Filipinos from nationals to aliens. Per the Asian Exclusion policy in the Immigration Act of 1924, immigration of Filipinos was now limited to 50 per year. Those who came could not become U.S. citizens or own land under Alien Land Laws in Washington and California. During this time, Filipino pioneers from the large second wave immigration were raising the second generation, or Bridge Generation, of Filipino Americans.

WORLD WAR II and Independence

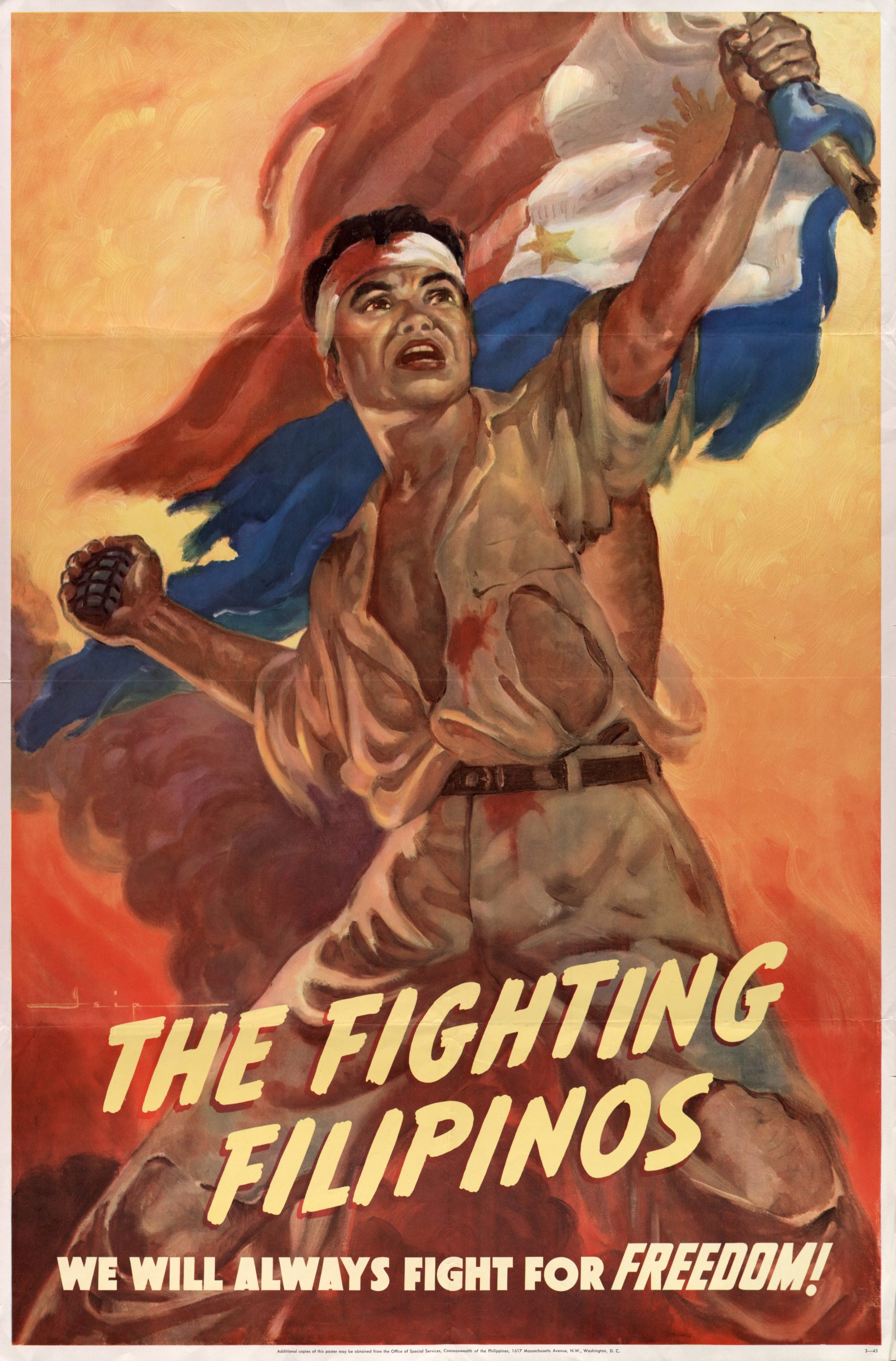

During WWII, anti-Filipino American sentiment was suspended, and immigrant suspicion and animosity were redirected to Japanese Americans. Once “little brown monkeys,” Filipinos were now fondly referred to as “little brown brothers.”

Over 200,000 Filipinos living in the Philippines and the U.S. enlisted in the military. Filipino aliens living in the U.S. were recruited into segregated Army units. They rose to the occasion and fought with the promise of citizenship to a country that they had already been citizens of in their hearts for decades. Over 10,000 of those who served were granted citizenship and GI benefits. The War Brides Act allowed the soldiers to bring their wives and children back to the U.S.

The United States quickly backed down on their promises when the war was over. The Rescission Act of 1946 stripped Filipino war veterans of their promised benefits and retroactively classified them as aliens.

On July 4,1946, the United States relinquished control of the Philippines and granted the country independence as outlined in the Tydings McDuffie Act.

Filipino Americans in Kitsap County

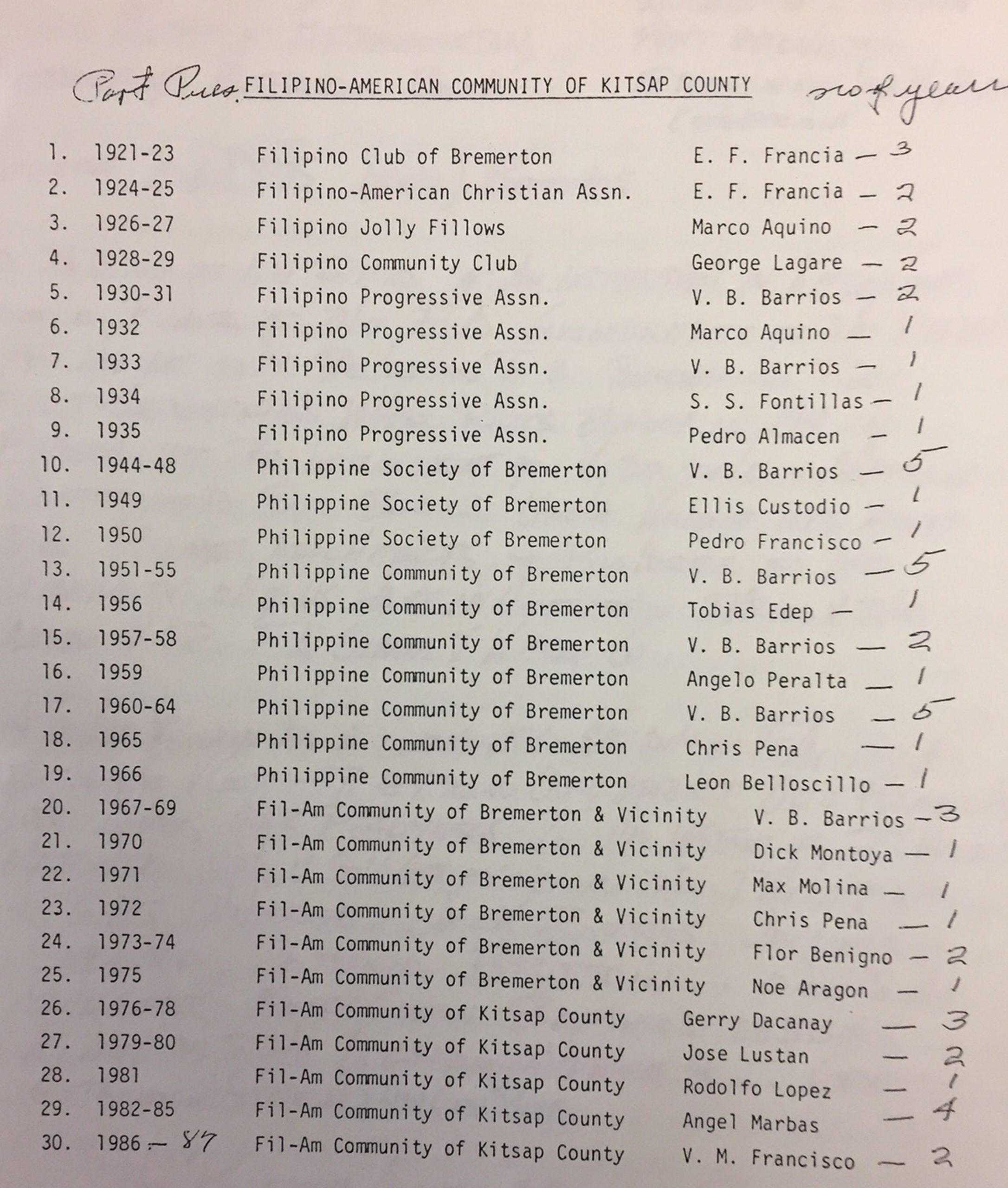

The oldest Fil-Am community in Washington state is right here in Bremerton. The current Filipino American Association of Kitsap County was established in 1921 as the Filipino Club of Bremerton. The group unofficially came together in 1914. This list of presidents through 1987 is used with the permission of the Filipino American National Historical Society in Seattle.

Shown here is the 2nd installation at Quizon Lodge no. 3 at Labor Temple, Bremerton, 1948. (KHM archives)

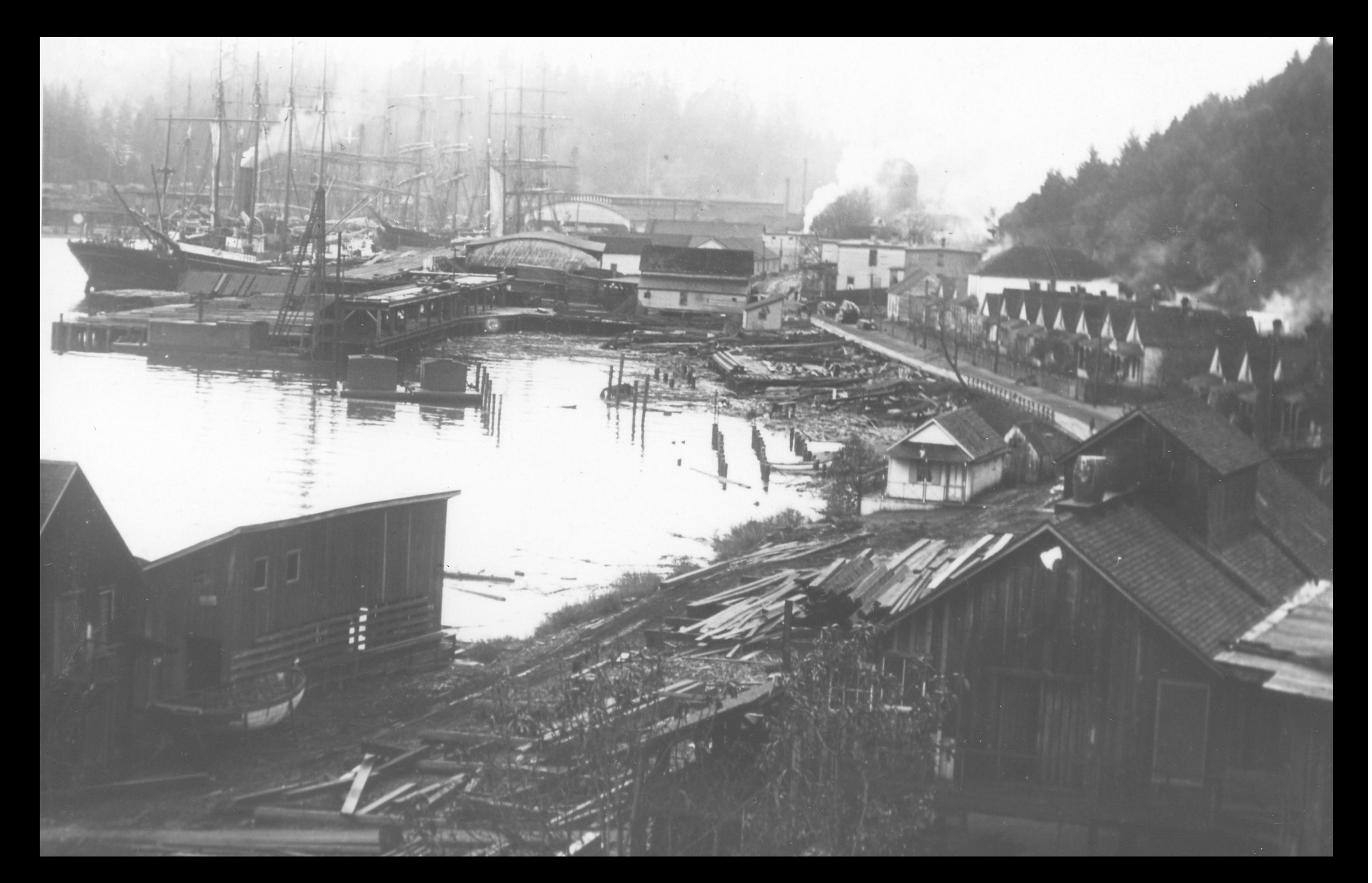

The first known Filipino in Washington Territory was a sawmill worker in Port Blakely. He was listed as “Manilla” in mill documents in 1883.

Port Blakely Mill c. 1900. KHM archives

The Filipino American Community of Bainbridge Island and Vicinity was established in 1943, although Filipino Americans have lived and farmed on the Island since the 1920s. The organization’s Hall is on the National Register of Historic Places and is still a vibrant gathering place for the community.

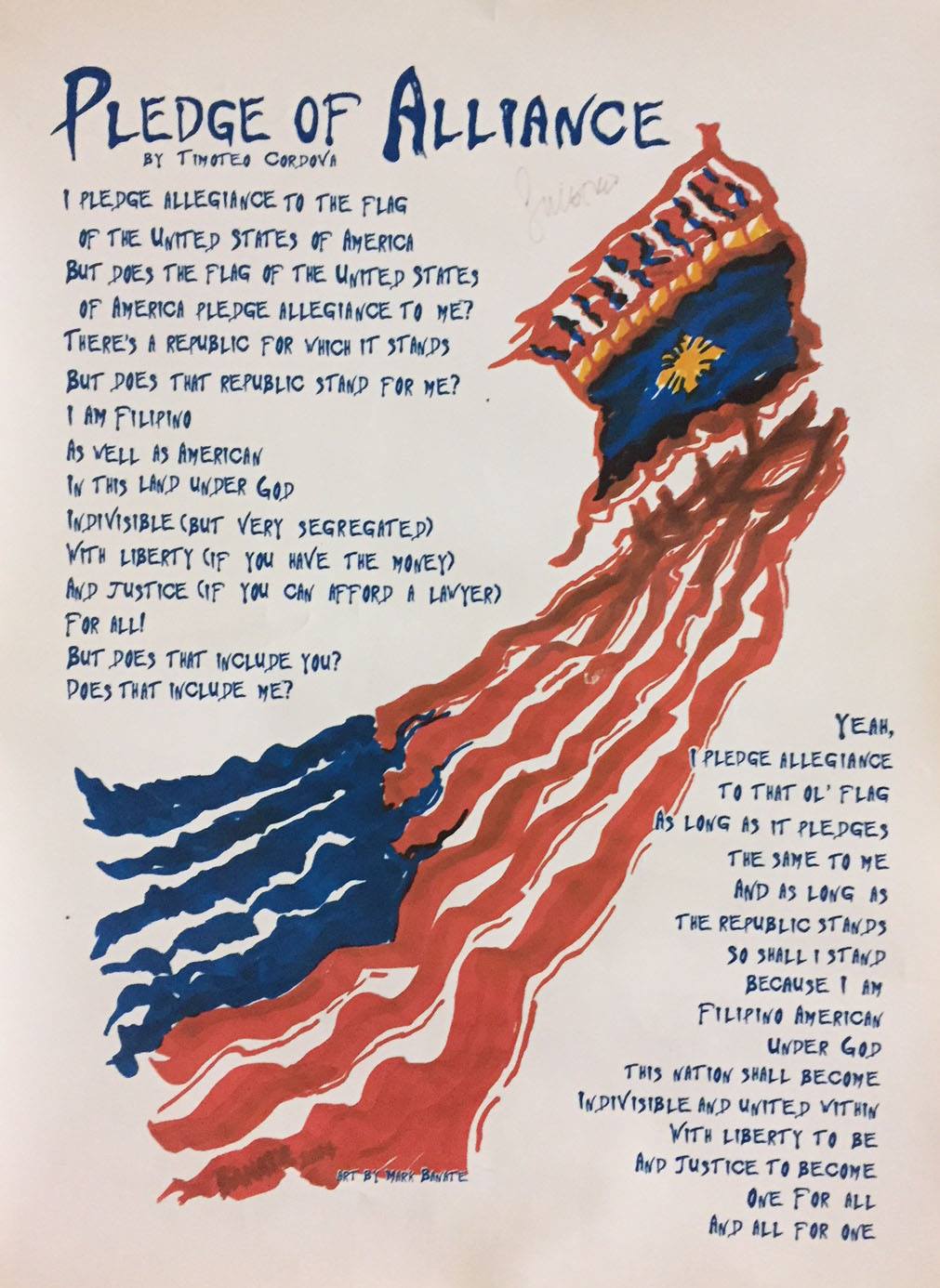

“The Pledge of Alliance” by Timoteo Cordova. Artwork by Mark Banate. The original piece is on exhibit at the Filipino American National Historical Society in Seattle. Used with permission.

Acknowledgments

This exhibit was developed in consultation with Filipino American historians and community members to ensure an accurate narrative. We researched resources written and created by Filipino Americans. This is not our story, but we are honored to present it.

Deepest gratitude to the following people for their contributions to this exhibit:

Dr. Dorothy Laigo Cordova, FANHS Director

Eli Avellanoza, Graphic Designer

Lani Oligario Burley

Joann Oligario

Gilda Corpuz

Gina Corpuz

Pinky Madayag

Doreen Rapada