HISTORY OF THE PUGET SOUND MOSQUITO FLEET

Before early settlers of Puget Sound were able to forge roads through the thick wilderness and build bridges across the rivers and straits, transportation was limited almost entirely to water travel.

Entrepreneur boat owners quickly began offering passenger service, mail delivery, and freight hauling. Spurred by demand and plenty of lumber for boatbuilding and fuel, more and more steam powered vessels plied local waters until Puget Sound boasted the largest Mosquito Fleet in the world.

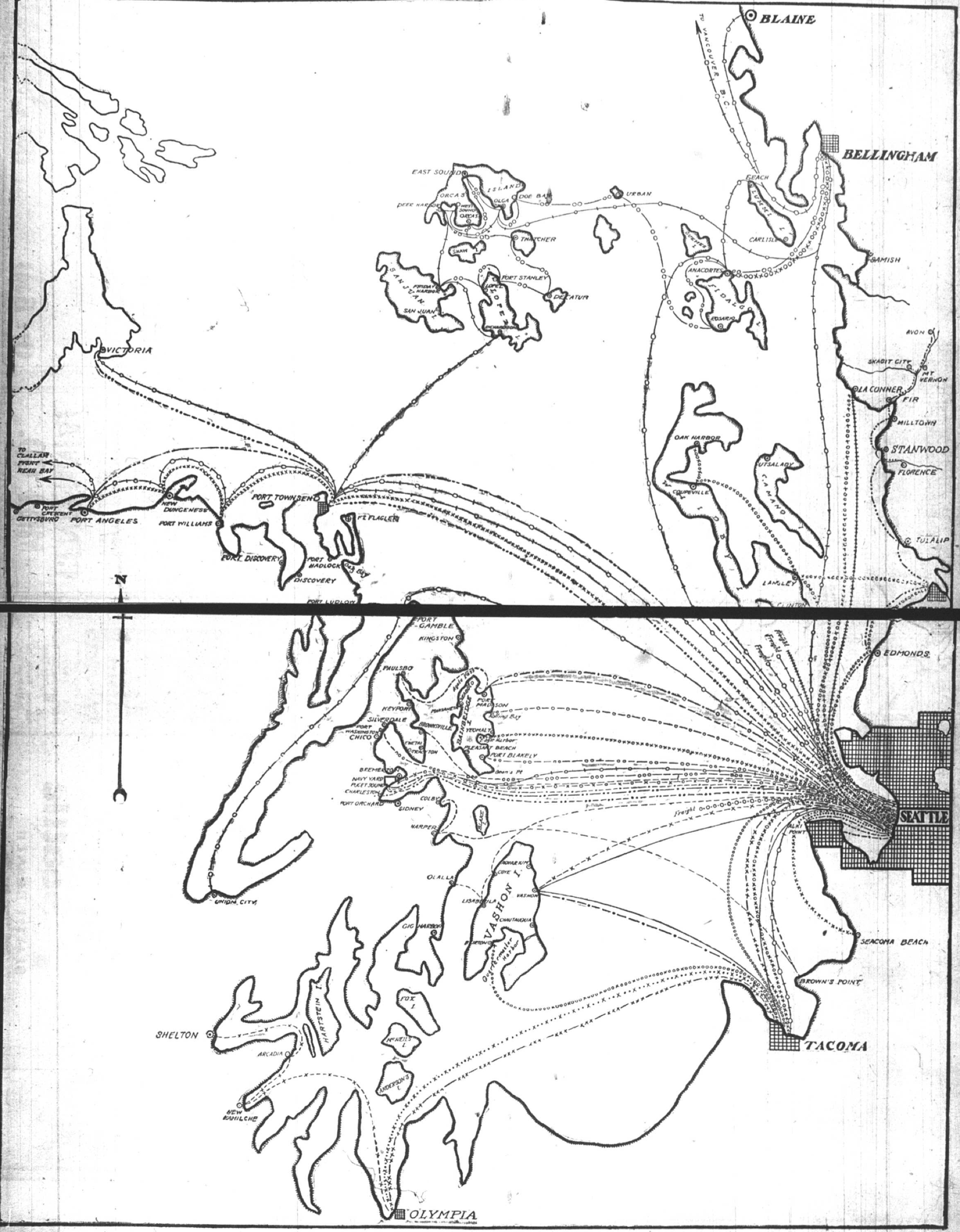

The Kitsap region was particularly dependent upon the Fleet. Situated between Puget Sound and Hood Canal, Kitsap County has over 200 miles of saltwater coastline. These waterways served as aquatic highways supporting the coastal communities.

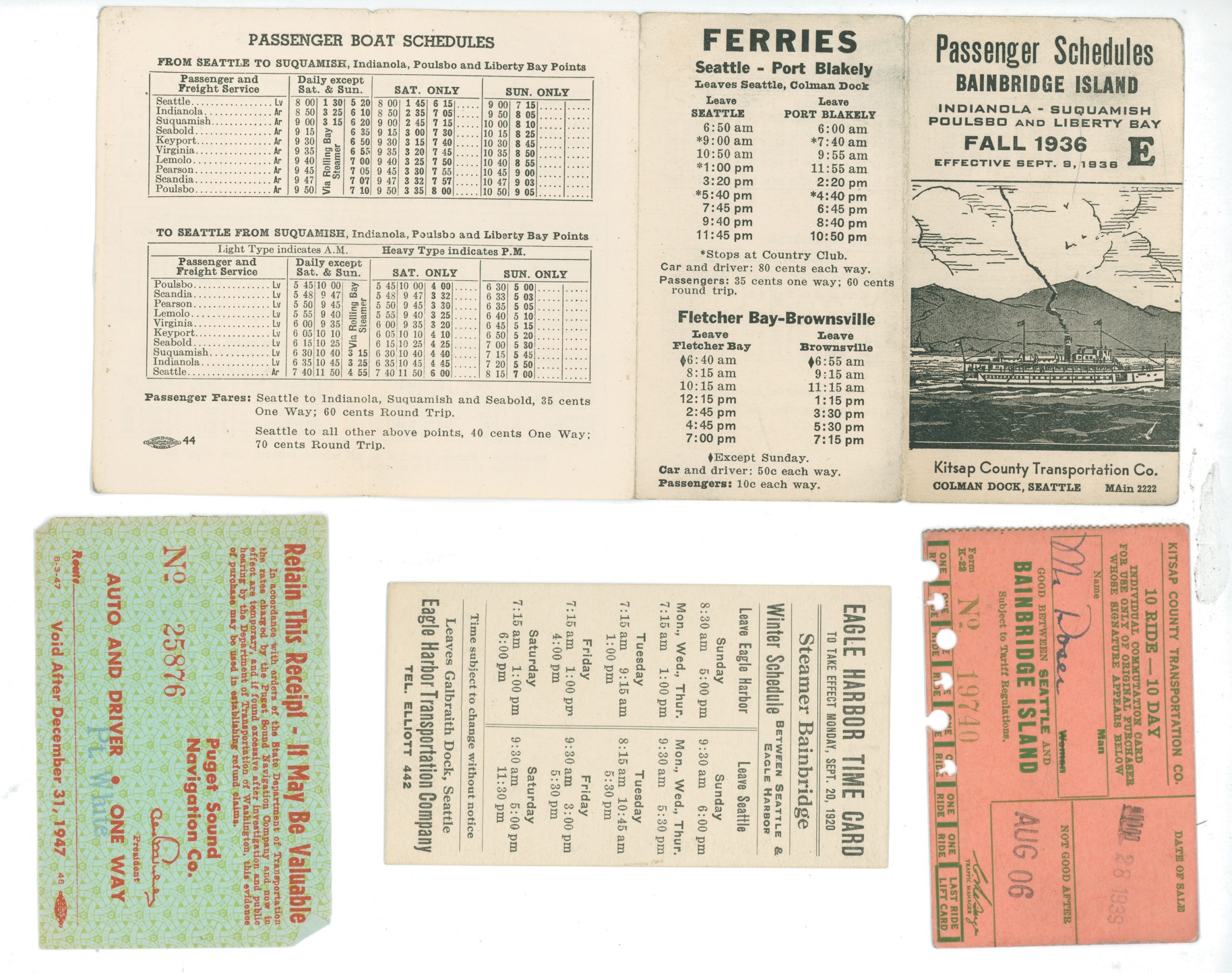

The steamers carried passengers, supplied stores, and moved livestock. Early vessels made impromptu stops wherever someone ashore signaled for a ride. Later, more standard itineraries and schedules emerged. The steamboat business drove economic development and supported emerging communities throughout the region. As towns and cities grew, commuter routes such as the Navy Yard Route between Seattle and Bremerton had to increase ridership with larger, faster boats anad compete for customers with other companies. The end of this era came with the introduction of car ferries and eventual consolidation by the Washington State Ferry System.

The Mosquito Fleet was central to the development of our region. Many vessels were closely tied to their communities. Their stories include social histories as well as the maritime and economic history of the era. Though the fleet is gone, Kitsap can boast the only two remaining vessels from that era.

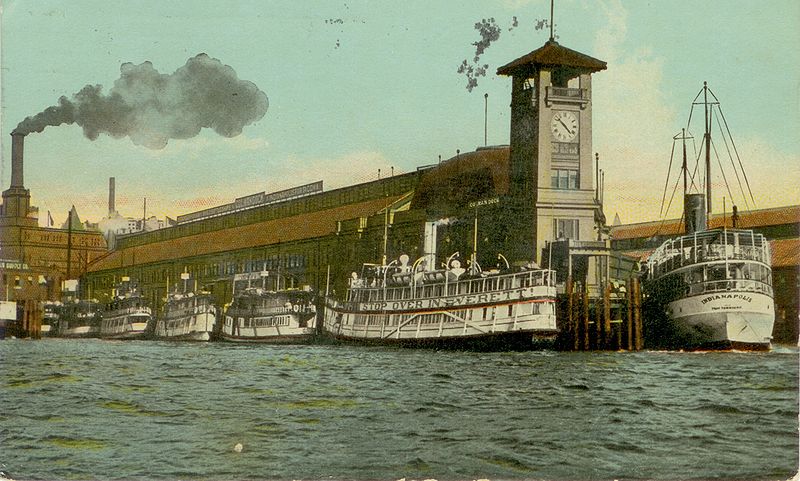

Along the various shorelines of Kitsap County, one can see remnants of what were once docks. Solitary pilings, abandoned and decaying, mark the places where a fleet of small vessels, fondly remembered as the Mosquito Fleet, stopped to pick up passengers – transporting people and their goods between the bustling and growing metropolises of Seattle and Tacoma and the smaller, more rural, communities that dotted the Puget Sound.

Communities with picturesque names like Suquamish, Indianola, and Olalla were less isolated then. They had direct links to Seattle. By stopping at every waterfront community where there was a dock or a float, the fleet supplemented the larger steam-powered stern- wheelers and sideheelers. Some of the boats were even able to beach themselves in order to load passengers and freight. Eventually, the smaller, agile vessels became the mainstay of sound transportation and remained so until the demand for auto carriers led to the next stage in ferryboats in the 1920s.

Mosquito Fleet vessels are often recalled as “jaunty,” “trim,” or “smart.” They were, in reality, practical. By transporting passengers, mail, livestock, and freight from just about any shoreside community that could build a dock or place a float where the vessels could stop, the boats played a direct role in the development of Puget Sound towns. Places that could not have existed in the isolation of the heavy forests and absence of roads prospered because they were linked to bigger metropolises. Their link, the Mosquito Fleet, used the water highways provided by nature.

The original, if unofficial “fleet” was made up mostly of sidewheelers and sternwheelers, while the boats of the late period were propeller driven steam ships. Size was not a classifying factor since boats varied from 30 feet to more than 200 feet in length. Most measured on the average of 100 feet and carried around 300 passengers. Using the broad definition, the number of Mosquito Fleet vessels has been estimated at 2,500 boats. At the turn of the century, the steamers were serving approximately 25 routes on the sound.

Mosquitos?

A popular myth tells of a Seattle newspaper man, looking over Elliot Bay at rush hour, and noting that the traffic on the water resembled a “fleet of mosquitos.”

In fact, the term was in use long before, originating somewhere in Europe. It appears in the Oxford English Dictionary with a citation from 1804:

“Man and victual the Musquitoe Fleet

(as Wit in his wantonness has described it).”

– Joshua Larwood, in “No Gunboats or No Peace!”

The Mosquito Fleet: Mass Transit of Early Kitsap County

Along the various shorelines of Kitsap County, one can see remnants of what were once docks. Solitary pilings, abandoned and decaying, mark the places where a fleet of small vessels, fondly remembered as the Mosquito Fleet, stopped to pick up passengers – transporting people and their goods between the bustling and growing metropolises of Seattle and Tacoma and the smaller, more rural, communities that dotted the Puget Sound.

Ferries

Black Ball Line: Dominance on the Water

Out of a handful of transportation companies, two were worthy opponents: the Kitsap County Transportation Company and the Puget Sound Navigation Company. By the 1930s, they had each successfully absorbed a number of other companies servicing the same routes. In the turmoil of the Great Depression and the labor movements spawned by economic necessity, one company emerged as the major ferry transportation company. Puget Sound Navigation, or the Black Ball Line, achieved dominance in 1936 and maintained a virtually unchallenged position until the State of Washington took over in 1951.

Kitsap County Transportation Company: The White Collar Line

Kitsap County Transportation Company, one of the two competing powers on Puget Sound, stemmed from Warren Gazzam’s consolidation of the pioneer steamboating companies operating in the North Kitsap area. Starting in 1905, KCTC eventually acquired or eliminated from business the Moe Brothers, Hanson Transportation Company, the Liberty Bay Company, and the Poulsbo Transportation Company. Colonel Gazzam as he was known in Kitsap County, was one of the most bitter rivals of Puget Sound Navigation’s Joshua Green. Between 1903 and 1923, the Black Ball Line (Puget Sound Navigation) and The White Collar Line (Kitsap Country Transportation Company) competed ruthlessly. Green’s company, enhanced by former Great Lakes steamers, had the bigger vessels. Gazzam relied on smaller and faster vessels and on technological innovation. The first diesel-powered passenger vessel, Gazzam’s 92-foot Suquamish launched in 1914, was an example of one-upmanship.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression: An End Comes to Competition on the Water

The arrangement enjoyed by the two remaining lines was upset by the Great Depression of the 1930s which caused the same economic downturn in the Northwest as it did in the rest of the country. It was fertile ground for union organizing and ferry workers eagerly signed up in the hope of attaining the level of wages that prevailed on San Francisco Bay ferries.

In November of 1935 the ferry-based unions struck Kitsap County Transportation Company. Knowing it would ruin the opposition; Captain Peabody of the Black Ball Line tried to avert the strike, and ultimately offered to share any windfall to PSN from increased revenue during the strike. The White Collar Line responded with an offer to sell-out. By that time Black Ball had also been hit by strikes and most service on Puget Sound was halted by a thirty-three day work stoppage. Black Ball weathered the strike and was able to acquire Kitsap County Transportation Company by agreeing to assume $140,000 in liabilities.

The Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet Lines

Map of Puget Soud